|

Stephen

Barber & Sandi Harris, Lutemakers

|

|||

|

Catalogue

and Price List 2017

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

The Vihuela and the Viola da mano

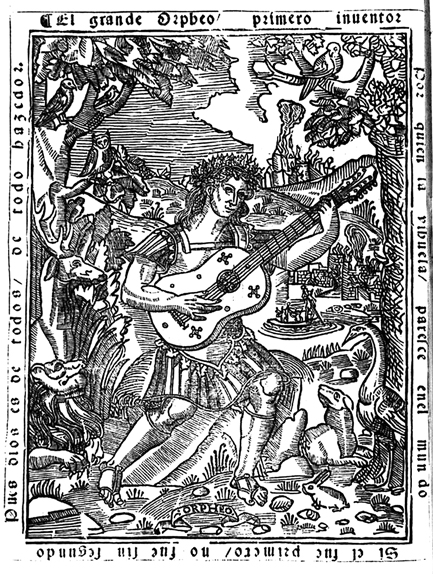

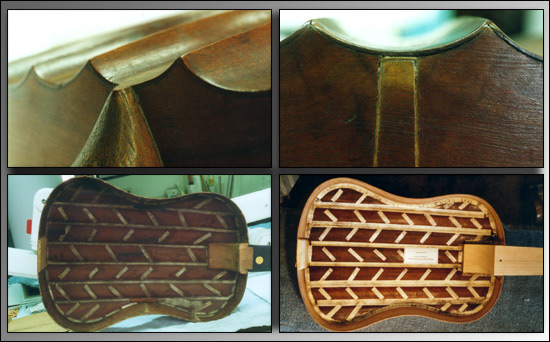

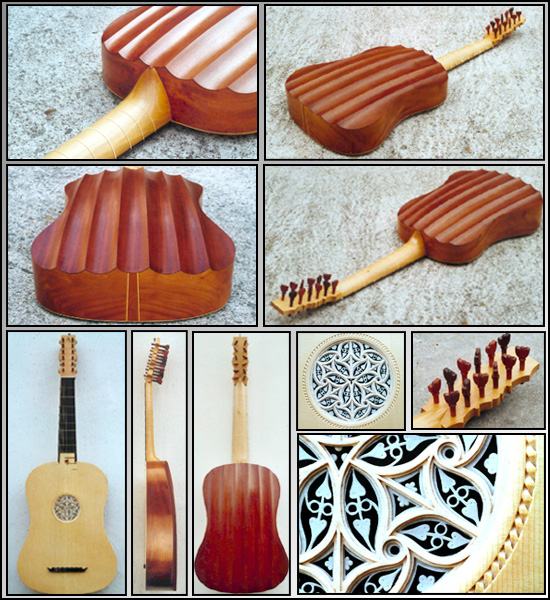

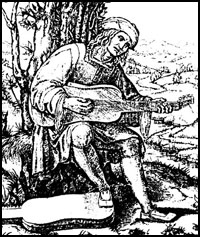

Above are three views of the copy of the 'Chambure' vihuela (E.0748) which we built in 2010, commissioned by the Cité de la Musique, Paris, who own the original vihuela; they asked us for a playable close copy of this unique, prestigious instrument. Its back is made from seven deeply-fluted, double-curved ribs of Jujubier (Jujube wood, Zizyphus sp.); the sides are also Jujube. The neck is cypress (with the neck, heel, internal 'slipper' block and pegbox all carved from the same piece of wood) and all details are copied from the original, using the same materials, dimensions and construction techniques; we were fortunate to find a piece of spruce for the soundboard with an almost identical number of year-rings as the original's, and the Musée staff tracked down the very elusive Jujubier on Corsica. Interestingly, our soundboard reacted and produced an almost identical set of results to the original, when subjected to the tests described in the Cité de la Musique publication: 'les cahiers du musée de la musique 5', "Aux origines de la guitarre: la vihuela de mano", under the heading 'La modélisation par éléments finis' on pages 81 and 82. (Photography by Tim Platt, imaging by Richard Harris). .Introduction The vihuela is one of the most interesting and intriguing historical plucked stringed instruments; it is first mentioned in the 15th Century, in the Kingdom of Aragón. It seems clear that it subsequently enjoyed widespread use in Spain and Portugal – and Italy – and across a greater swathe of the social order than was suspected up until only a few years ago. All of us who make and play these instruments today owe an enormous debt of gratitude to modern researchers such as Antonio Corona Alcalde and John Griffiths; Antonio states in his 1995 essay 'The Popular Music from Veracruz and the Survival of Instrumental Practices of the Spanish Baroque' that the vihuela was played throughout the whole social gamut in Spain and zones of Spanish influence – yet there remains the enigma that an instrument which was perhaps in its heyday more widely played than any other in Spain has survived to us in the 21st Century represented by but three known extant instruments and only seven printed books of dedicated music. John Griffiths – like Antonio, a player/scholar/researcher – has also contributed an enormous amount to our understanding of the vihuela, and has been particularly thought-provoking with his researches into the socio-historical aspects of the instrument and those who played it. The famous woodcut depicting Orpheus playing a 6-course vihuela, from Luis Milan's El Maestro, (1536). The surviving instruments There are but three known surviving instruments that are generally considered to be vihuelas; this is an extraordinary state of affairs, considering the historical flowering and importance of the vihuela in Spain and Portugal, and its likely subsequent use in Central and South America. Those of us wanting to make vihuelas have therefore but a very few old instruments to refer to, compared to lutemakers, who have a wealth of material to draw upon and study, with several hundred instruments having survived (although the fact that only two 6-course lutes have survived with their original necks, soundboards and pegboxes is perhaps a parallel and echo to the lack of surviving vihuelas, the contemporary of the 6-course lute). There have been suggestions from time to time over the years, and again more recently, to claim the 5-course guitar by Belchior Dias in the Royal College of Music museum, London, as a possible vihuela, but the rather late date of its label – 1581 – and its narrow neck and a pegbox fitted with 5 double courses (suitable for only 5 courses – and a tight string-band at that) mitigate against it being a vihuela – or indeed anything with 6 courses – by any honest and impartial examination of the original instrument (we deal with recent fanciful claims regarding the Dias under Footnotes, in Catalogue 14). The three instruments under consideration here are the well-known example in the Musée Jacquemart-Andrée, the recently re-discovered 'Chambure' instrument in the Cité de la Musique (both in Paris) and the rather enigmatic instrument in the Iglesia de la Compañiz de Jesús de Quito, in Quito, Ecuador. Not one of these three surviving instruments is dated, although the two Paris examples are accepted as being made during the sixteenth Century, and thus contemporary with the surviving printed books of pieces. We thought that it would be helpful to show a few images of these instruments here, for those unfamiliar with them; we'll add more images in the future. The Musée Jacquemart-Andrée 'Guadalupe' vihuela This instrument – which has no label or other identifying marks, save for the word 'GVADALVPE' branded on the bass edge of its pegbox – has been known to scholars, makers and players for several decades, since it came to light early in the twentieth Century. It is a large instrument, with a string length 0f 798mm (measured from the marks of the six-course bridge it was originally fitted with) and probably represents a guild examination masterpiece. Conservation work by Pierre Abondance in 1978 was the first time the instrument had been worked on by a skilled modern restorer, and Pierre thankfully provided the rest of us with splendid drawings of the instrument at the same time.

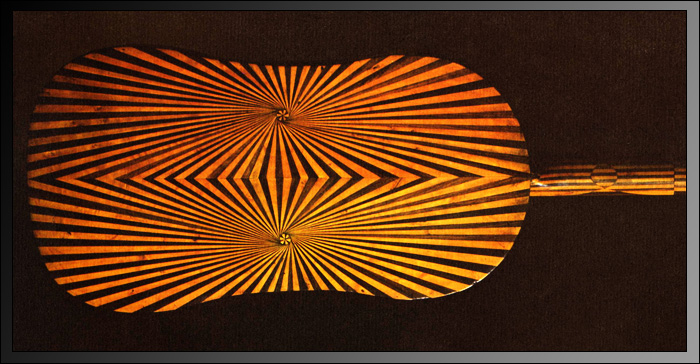

The image above shows the famous and iconic design of the back of the 'Guadalupe' instrument; the double-sunray design – mirrored along a horizon which is also the centreline – is made from alternating darts of European boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) and a rosewood species (which Pierre Abondance has identified as probably kingwood – Dalbergia caerensis). The neck is also made of sections of boxwood and kingwood sandwiched together; it is made in one piece with the heel, neck-block and pegbox – the same 'one-piece' construction is used in the Quito instrument, and the 'Chambure' vihuela. These three instruments represent the earliest known use of this type of integral neck construction, which was employed in a large number of later Iberian guitars. The 1581 Belchior Dias guitar also has this feature.

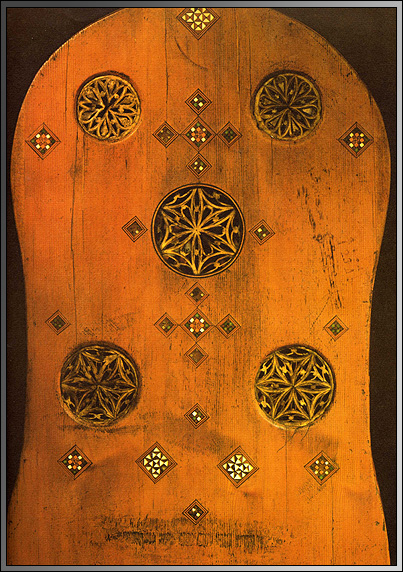

The 'Guadalupe' vihuela is a large instrument; the most likely explanation for its high level of decoration is that it was originally made as a 'masterpiece', possibly under examination regulations for entry by its maker to a guild. The five rosettes and numerous inlaid mosaic squares with which its spruce soundboard is adorned have intrigued and inspired instrument makers for decades. The idiosyncratic nature of these inlays, which range from the single motif centrally-placed at the top of the belly near the fingerboard, to smaller motifs in all 4 corners of the soundboard – and many more besides, as this lavishly-inlaid Jacquemart-Andrée instrument demonstrates – were well-known enough for a traveller in Venice, in the Viaje de Turquia attributed to Cristóbal de Villalón, to describe mosaics he sees there: ". . . thus, over this figure they place their small square-shaped pieces, as the violero does with his inlays ". Vihuela soundboards seem to have been frequently adorned with marquetry decoration – here in the form of inlaid contrasting woods and other materials such as plain white bone as well as green-stained bone, for example – a material also employed, interestingly, in the fabulous lira da braccio by Giovanni d'Andrea, made in Verona in 1511 (Vienna KHM No. C94) where it is used in fingerboard inlays as well as soundboard inlays. The style and execution of the inlays of the soundboard in the Jacquemart-Andrée vihuela are also very similar to the eleven motifs – also 'square-shaped' – found on the anonymous bass viol in the Hill Collection, in The Ashmolean, Oxford (Hill No.3), in their use of green-stained bone; they are also very similar to those found on a harp in the Wartburg, Eisenach. This perhaps suggests an interesting cross-fertilisation of decorative design, or possibly a common origin or source for the inlays.

Perhaps one of the most significant pieces of evidence – clearly visible in the image above – is the scar left by the missing bridge: it was clearly made to the same basic design as the bridge of the 'Chambure' and Quito instruments, in having 'windows' cut in it for the strings, rather than having holes drilled in it, as the bridges of contemporary lutes had. The rectangular areas of torn grain where the original bridge's 'feet' were glued to the soundboard can be clearly seen.

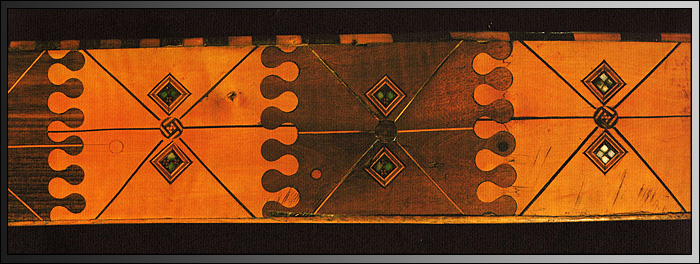

Above: a close-up of the bass side of the instrument, near the waist; the sides are made of interlocking panels, which are all inlaid with similar square motifs and lines. They are also made of boxwood, again contrasted with kingwood (far left panel, in this view); Pierre Abondance suggested on his original 1978 drawing that cormier (sorbus sp.) is used in one of the darker panels on each side (the central one above, for example) although an identification as mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) has been suggested more recently. An example of the characteristic type of knot found in boxwood can be clearly seen in the upper right half of the second panel from the left (wind instrument makers usually groan when one of these appears at the lathe). The plugged holes which can be seen in the two central panels are thought to be evidence of the use of an internal mould. Later guitars exhibit such plugged holes (for example, the Stradivari guitars of 1680, 1681 and 1700). One of Stradivari's surviving guitar moulds has little wooden pegs still protruding from its surface at the waist, as though they were left behind when the last guitar was made on it; they coincide pretty well exactly with where the plugged holes appear on the 1680 and 1700 instruments.

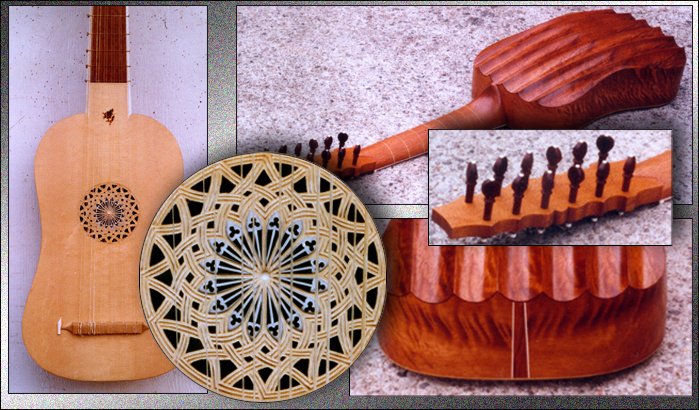

The 'Chambure' vihuela in the Cité de la Musique (E.0748) This instrument was first drawn to public attention by Joël Dugot, in 1998. It had lain forgotten and effectively mis-catalogued in the depot of the old Paris Conservatoire collection, having been bequethed by the late Geneviève Thibault, Comtesse de Chambure. Perhaps one of the most important organological discoveries for decades, this instrument presents the clear impression of having been originally constructed with a serious player in mind, rather than a rich dilettante. It is made from local materials native to the Iberian peninsula: it has a cypress neck, and back and sides from jujube – a fruitwood – rather than exotic, expensive imported materials. Its soundboard is unadorned except for a beautiful inset rose, made of wood backed with parchment. In September 2010, we delivered a copy of this instrument to the Cité de la Musique, which was commissioned from us by them, so that they would have a playable example. The copy was made using the same timbers as the original, and its first public showing was at a conference in the Musée on November 27th 2010.

The lower 2 images (above) show the inside of the back of the original on the left, with, to its right, the inside of the back of our first copy; the little diagonal strips across the ribs are parchment, as are the corner strips between the side and back ribs. The slender spruce bottom block and the one-piece neck & slipper block are clearly visible in both instruments; the carving and shaping of the original's slipper block are so similar to that of the Dias guitar, that we are sure they are at the very least from the same workshop, if not the same hand.

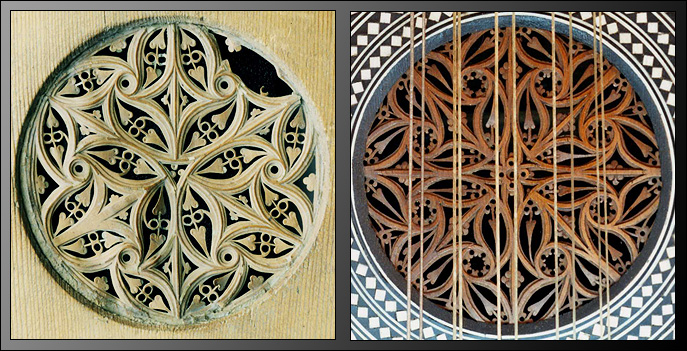

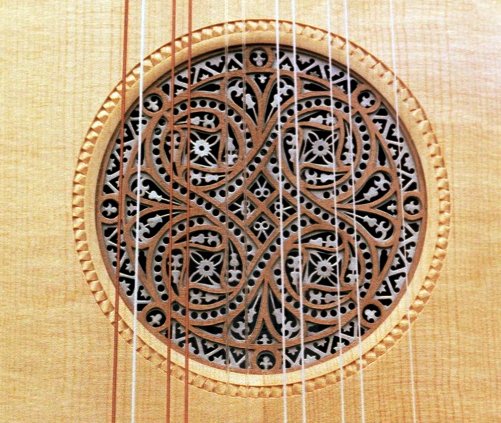

The two images above show the original instrument's rosette (the missing section to the right in each view helps to orientate the viewpoint - the soundboard was rotated through 180û between the two photographs). Its structure - two layers of wood backed by one layer of parchment on the inner surface - is clearly visible; the parchment layer carries cut and punched filigree detailing. The outer, upper surfaces are covered in a thin layer of paint or possibly gesso (was the original intention to gild it ?) whilst the inside view shows the parchment curling away from the timber in places, with the undulating distortion of the rosette due to the effects of age and fluctuating humidity unmistakable.

The rosette of the 'Chambure' vihuela (left) has certain similarities with the rosette of an anonymous guitar in the Vienna KHM collection; the basic elements of the pattern are apparent in both designs, the vihuela's rosette being generated on a multiple of three, whereas the guitar's is based upon a multiple of four. The guitar rosette is made from two layers of wood, the vihuela's from two layers of wood with a bottom layer of parchment. It is interesting to speculate on the origins of the two designs (and indeed the rosettes themselves) given what we now know of the trade in pre-made rosettes and entire soundboards between the early instrument makers across Europe. The guitar rosette was probably made several decades after the vihuela's. The Quito vihuela The third example is claimed to be a relic of Saint Mariana de Jesús (1618-1645); there is apparently continuous documentation to support this attribution. The instrument is kept in the Iglesia de la Compañiz de Jesús de Quito, and because of the hitherto near-impossibility of its availability for close study by scholars and organologists and its extremely fragile condition, it had not been comprehensively examined. Donald Gill published a monograph on the instrument entitled A Vihuela in Ecuador in the Lute Society Journal in 1978; this article was illustrated with black line drawings (but no photographs) by Oscar Ohlsen. Confusingly, Oscar draws what look like holes in one view of the bridge, and cut-outs/slots in the other, with no accompanying explanation. Diana Poulton had earlier published an article – also entitled A Vihuela in Ecuador – in the LSJ in 1976. Nothing further was published concerning the instrument until 1991, when Egberto Bermudez contributed an article to the catalogue of the 1991-92 exhibition La Guitarra Española; this included but one tantalising colour photograph, a slightly oblique view of the front of the instrument (reproduced twice, on pages 24 and 32 of the catalogue, at different scales). Interestingly, Egberto erroneously states that the Quito instrument's bridge has holes for the strings; he seems to have failed to observe the rectangular cut-outs with which it is actually fitted (perhaps he had been expecting to find drilled holes, or didn't have time to look more closely?). He did, however, correctly observe that the instrument's neck and pegbox (and heel & block) were carved from one piece of wood – a fact subsequently confirmed by Ariel Abramovich in 2005. Thankfully, our good friend Ariel – a vihuela specialist – was able to take some new photographs of the instrument over the summer of 2005, which have revealed some very interesting features. For example, the bridge has 'window' cut-outs for each course of strings, cut in a 'letter-M' shape very similar to the bridge of the Cassas Baña guitar in the Brussels MIM collection (this instrument being a 5-course guitar probably made later in the 17th Century). The influence of Iberian guitar design is apparent, with stylistic pointers to the later Cadiz school in the handling and design of the inlaid decoration.

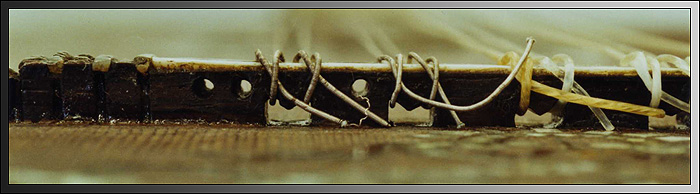

Above: an oblique view of the bridge of the Quito vihuela, the image kindly supplied by our friend Ariel Abramovich. The M-shaped cut-outs/slots to hold and guide the strings are clearly visible, as are what appear to be indentations from the first two courses of strings (perhaps indicating that metal strings were fitted at some point?).

Above: a close-up of the bridge of the Cassas Baña 5-course guitar, probably built contemporaneously with the Quito instrument, or later; the same M-shaped cut-outs are clearly visible. The three large holes visible here were probably a later addition; what is also clearly visible here is the gradual diminution in height of the cut-outs from bass to treble – a feature of both bridges. Both bridges are quite narrow, and seem to be original, and to have never come away from their respective soundboards. Many consider the Quito instrument to be a candidate to be accepted as a true vihuela, possibly constructed in the early seventeenth Century; with great prescience, given the ongoing controversies surrounding the vihuela and early guitar, Donald Gill commented back in 1978: "It does not seem likely, therefore, that the six-course guitar developed prematurely in Ecuador, but rather that the settings of religious music from the old vihuela books were still being played in places like Quito by people of intense religious convictions such as Saint Mariana de Jesús". There is contemporary evidence that Saint Mariana played the instrument, and that performing upon the instrument was a significant part of her life, hence its status as a holy relic. However, it does seem most likely that this instrument represents a later school of building than the 'golden period' associated with the flourishing of the instrument during the period spanned by the seven known books of dedicated music, and may even represent a paradigm of a flourishing South American school, using ideas (and perhaps even components and materials) from the Old World. The presence of a bridge with slots cut through it to hold and guide the strings is very interesting, as this feature not only appears on the Chambure vihuela and the Cassas Baña guitar (above) but on later instruments by the Voboam family. The repertoire The printed books which have survived are, in chronological order: El Maestro by Luis Milán (1536) Los seys libros del Delphin by Luis de Narváez (1538) Tres Libros de Música by Alonso Mudarra (1546) Silva de sirenas by Enríquez de Valderrábano (1547) Libro de música de Vihuela by Diego Pisador (1552) Orphénica Lyra by Miguel de Fuenllana (1554) and El Pamasso by Estevan Daça (1576). Daça's El Parnasso – the last of the extant printed books – was published when he was thirty-nine years old, according to John Griffiths, and apparently contrary to the advice and wishes of his father (who later relented when he realised that it was a success and a decent enterprise). Modern players are now – thanks to the magnificent, recent work of Gerardo Arriaga – able to access the pieces contained in all seven books on one CD-ROM.

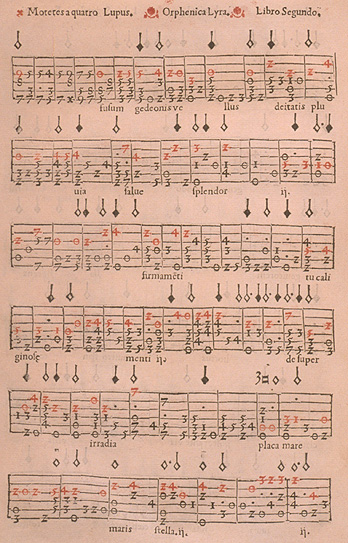

Above: tablature from Orphénica Lyra by Miguel de Fuenllana (1554). The red numerals (cifra colorada) printed in the tablature of the piece shown above indicate the voice part. Many modern facsimiles are in monochrome, and thus neglect to show this important feature, leaving the player obliged to work out the vocal line; in the original printed versions, it was made clear, as can be clearly seen in the example shown above. Much of the repertoire contained in these books will be very familiar to modern lutenists, not least because the vihuela and viola da mano appear on the title pages of tablature devoted to other instruments including the lute. Interestingly, two of the 'celebrated seven' vihuelists include pieces for the four-course guitar: Mudarra's 1546 book contains the first appearance of pieces for a four-course instrument called a guitarra, and Fuenllana also includes a small number of pieces in Orphénica Lyra.

Above: the title-page from Fuenllana's Orphenica Lyra, published when he was still in his early twenties. The great Italian lutenist Francesco Canova da Milano is thought to have held the Viola da Mano in equal esteem to the Lute; there are the printed works for viola or lute by him, Intavolatura de Viola o vero Lauto . . . Libro Primo della Fortuna and Intavolatura de Viola o vero Lauto . . . Libro Secunda, both published in Naples in 1536 (the same year that Milán published El Maestro. – it is thought that Luis Milán visited Francesco shortly before both books were published). There also exist contemporary accounts of Francesco performing on the Viola da Mano; and listed in the musical instrument inventory of the Augsburg banker, Raymond Fugger, compiled in 1566, as item 56, is a viola alla Neapolitana. Around half a century later, in two inventories listing the musical instruments owned by Cesare d'Este (dated 1600 and 1617) there is recorded, firstly in 1600: "one viola alla Napolitana with its walnut case . . . one viola alla Napolitana with its walnut case, similar to the other one - with nearly two decades later, the 1617 inventory listing "Viole all Napolitana with their walnut cases, two". It has been suggested that both inventories refer to the same instruments. Our initial approach For many years, we had resisted the temptation to design and build a vihuela – which had always perforce meant working from iconography and the single surviving accesible instrument then known, the Jacquemart-Andrée Guadalupe example – because there was little serious interest in playing the instrument's repertoire on a vihuela; it had been the subject of a lot of unseemly squabbling between lutenists and classical guitarists, and between lutemakers and guitarmakers. Despite this rivalry and confrontation, little progress seemed to have been made in producing an instrument that may have reflected what the composers of those seven books had in mind. The only light in the darkness was the appearance of a series of essays and articles written by Antonio Corona Alcalde, which set us thinking again. So back in 1987, not having made a vihuela for ten years, we decided to make a fresh start on an instrument, in fact a viola da mano type, with a vaulted back and sickle-shaped pegbox. This was inspired by the published researches of Antonio. We first exhibited our recently-completed prototype at the Utrecht exhibition that year, and although we had only put its strings on at the exhibition, it was nevertheless snapped-up there and then by Hans-Michael Koch, the Hannover-based lutenist and guitarist, who was convinced by its sound and potential. Shortly afterwards, Julian Bream, visiting our workshop to have some repairs and adjustments made to his lute, saw one of these early prototype instruments sitting on the drawing-board, and asked if it was a baroque guitar; upon being told it was a vihuela, he chuckled and said: "They never work, I've yet to hear and play a convincing example". We invited him to go ahead and have a laugh, and try this one: he sat down and played the instrument for around 20 minutes, then announced that this was the first time he'd had in his hands an instrument capable of producing the 'vihuela' sound he'd always heard in his head, but had never found under his fingers, and promptly ordered one. Inspired and fired-up by Julian's encouragement and endorsement of the direction we were taking, we continued to work on designs for vihuelas and violas da mano, and went on to produce a large number of examples in the subsequent years.

In the image above, the backs of both instruments are constructed from cypress and walnut, the back of the vihuela in the background inspired by the design of the Jacquemart-Andrée 'Guadalupe' original. The fingerboard of the vihuela in the foreground is made from a marquetry of walnut and boxwood, the design based on a painting by Juan de Juanes [1523-79] La Trinidad con querubines y ángeles in the Convento de Santa Clara, Gandia (Valencia). These instruments are both versions of model No.1 below. We are grateful for the enthusiasm, research, writings and insight of Antonio Corona-Alcalde and John Griffiths, which inspired us to start making vihuelas all those years ago; and to Joël Dugot for drawing our attention to the Chambure vihuela. Vihueladaag, Utrecht Festival Oudemuziek, 31st August 2008

The image above was used as the title page of the August 31st 2008 Symposium on the vihuela – organised by our colleague and friend Carlos Gonzalez, under the auspices of the Sociedad de la Vihuela – as part of the Utrecht 2008 Oude Muziek Festival. The symposium was complemented by an exhibition held in the Kikker Theatre, Utrecht. The left-hand image is a vihuela rosette designed by us, which we have used on various instruments, including on No. 4 below; we were pleased to make use of the image available. We were delighted to have finally met John Griffiths in person at the Symposium, and to have been able to show him and other players present some of our vihuelas. Living on opposite sides of the planet does not always make such meetings easy to arrange; drinking a couple of beers afterwards with John by the Oude Gracht was a nice way of rounding-off our visit. The 'Chambure' Vihuela For the modern luthier, the problem of reconstructing a suitable instrument for the surviving Vihuela repertoire has of course always been complicated by the absence of a number of convincing intact historical instruments. The well-known (and large) 'Guadalupe' instrument in the Musée Jacquemart-Andrée, Paris, is probably a guild examination masterpiece, with a string length 0f 798mm (measured from the marks of the six-course bridge it was originally fitted with) whilst the enigmatic instrument in Quito (which itself has a string length of 720mm) – the subject of some very rough and indifferent repair work carried out around 1911-12 – awaits proper, definitive examination by an informed luthier or organologist. It could yet turn out to be the vihuela it is claimed to be, but equally it may be a locally-made South American instrument, from the late 18th/early 19th Centuries, and possibly a type of 6-course guitar, rather than a true vihuela; only dendrochronology would answer this question for certain, and there does not appear to be much chance of that happening in the foreseeable future; thus the jury has to be out on this one for the time being. Thankfully we now have another historical vihuela to refer to, radically different to anything previously suspected – yet clearly related to the earliest surviving dated guitar – via the discovery in 1997 of the instrument formerly in the collection of the late Geneviève Thibault, Comtesse de Chambure, in Paris. At the invitation of Joël Dugot, we travelled to Paris in April 1999, to examine, photograph and measure it in great detail, and subsequently finished a prototype copy of it in May 2001, and made several further copies and evolutions since. It has provided important clues and insight, and made us realise that the construction of vihuelas was probably far more subtle and varied than has been realised up until now. We were the first to discover and develop a reliable, consistent technique for double-bending its back ribs – and although others have since jumped on the bandwagon (the majority obviously working from plagiarised writings consequent upon theft of early development moulds we were working on in late 2000 (see the Footnote below for further details) we've built more of these instruments than any other modern makers. We are also responsible for everybody now referring to it as the 'Chambure'; we were the first to name it thus, in honour of its illustrious previous owner, the late Geneviève Thibault, Comtesse de Chambure; when we first posted images of our prototype copy back in May 2001, we announced it as the first copy of the Chambure vihuela. It's interesting to note just how many others who have built an instrument based on the original or written about it have adopted our suggested title.

The front view above, and the one on the left of the pair lying face down is the same instrument, a 7-course version of the Chambure vihuela; our first copy/prototype, a 6-course instrument, is on the far right. Owned by Dan Winheld, of Berkeley, California, USA. Although the evidence so far appears to suggest that the Iberian Vihuela usually had a flat back and pegbox with probably unison stringing of the bass courses, whilst the Italian Viola da Mano had a curved, vaulted back and a sickle-shaped pegbox, with octave stringing of the basses (like the contemporary 6-course Lute) considerably more research needs to be done to define these two schools of construction and playing with any certainty – especially since the Chambure vihuela has both a vaulted back and a flat pegbox, both features being absolutely original to each other. Who knows? perhaps another similar instrument might surface – 'miracles' do happen: a previously unknown lute by Laux Maler appeared in rural France in late 2003; it had been crudely converted to a 6-string 'guitar', and had languished in unrecognised obscurity for ages. But thereagain, the Chambure vihuela had for a long time been mis-catalogued as a sort of rustic guitar. . .

Vihuelas at dawn ! Two vihuelas, the flat-backed instrument laying face-up is a version of No.1 (below) and the vaulted-back instrument laying face-down with deeply-fluted back ribs is a version of No.5. Having built several copies of the original Chambure vihuela following completion of our first prototype copy in May 2001, over the summer of 2003 we completed our first 'evolution' model, a smaller version of this instrument, at 590mm for g' tuning (shown above alongside the earlier design, see also No.5 below) which allows access to some of the more demanding left-hand chords and stretches.

The image above shows (on the left) the first of our 'Evolution' versions of the Chambure vihuela, with our first copy of the Chambure on the right; a version of the related Belchior Dias guitar is in the centre. The next few Evolution versions will be in walnut, and an ebony example will follow when we have the time, since we are intrigued by the many references to the use of ebony in the inventories: the Marquis of Camarasa. who died in 1576, is mentioned as having owned "an ebony vihuela with ribs". This is one of many references to vihuelas "with ribs" and we are convinced that this confirms the prevalence of this structure; and the success of the instruments we have built this far – all with very clear, well-balanced and powerful tone – not 'introverted', as some makers have claimed for their versions – has been endorsed by those who have tried and ordered these models. The second version – at 590mm string length – has been played by several musicians at exhibitions in Utrecht, Bremen, Vienna and Regensburg - as well as here at our workshop in London – and they were all astonished by its power and clarity, combined with its light construction (it weighs significantly less than our original Chambure copy, which we have kept). We have built further examples and developments of this vihuela over the last few years, including the version shown below, in a' tuning, at 540mm string length; interestingly, the most recent version of this design weighs 600 grammes.

The image above shows details of the body of a vihuela tuned in a' (see No. 4 below for further images and description). Models currently available Seven-course versions of all the instruments listed below are available, at very slight extra cost.

1. Vihuela in g' (Own design, based on the 'Guadalupe' instrument in the Musée Jacquemart-Andrée, Paris)

Six courses; flat back and sides in walnut striped with cypress, walnut/ebony

or walnut/brazilwood (pernambuco); pegs in ebony alternating with brazilwood,

with bone pips; fingerboard in boxwood edged with bone; walnut neck

& pegbox; single inset rosette in wood and parchment, also available

with the addition of 4 smaller rosettes cut into the soundboard; fingerboard

also available in interlocking 'jigsaw' contrasting panels (ebony &

walnut) as the original instrument. This model is also available with a back constructed like the original, with over 200 pieces of alternating woods in a book-matched radiating design, in walnut/cypress, walnut/ebony or walnut/brazilwood (to complement the timber choices above). £4200

In the 2 images immediately above, the back on the left is constructed from cypress and walnut, the one on the right is from ebony and walnut. The fingerboard of the vihuela third from the left, top row, is made from a marquetry of walnut and boxwood, the design based on a painting by Juan de Juanes [1523-79] La Trinidad con querubines y ángeles in the Convento de Santa Clara, Gandia (Valencia). (with radiating 'sunray' design as above: £5000; inlaid fingerboard £500 extra) 2. Vihuela in a' (Own design, as above)

Six courses, design and construction options as above, single rosette.

This smaller instrument is preferred by some players because of the

ease of playing the more difficult chords which the shorter string length

allows. Some players also prefer the different touch and string tessitura

of this tuning. £4200

The 7-course instrument here was made in May 2004 for Paul Shipper, of NYC, who gave it its first public outing at the 2004 Regensburg Tage Alter Musik festival, where he was directing the ensemble Visceral Reaction in concert. Paul sent this email after getting back to NYC: "I hope you had a nice easy trip back to London. Chido (the vihuela) is doing fine, and enjoying his new gut strings. It was great to see you, and, again, a million thanks for the 'loaner' and the fantastic repairs. Did I mention that one of our encores was Chan Chan from Buena Vista Social Club, and I played bottleneck Stubbaphone ? Best, Paul". We should explain a couple of things here: the night before their Regensburg festival concert, we did some emergency repairs to a pair of instruments belonging to Visceral Reaction which British Airways had carelessly damaged in transit; and the 'Stubbaphone' – the 'loaner' – is a very decorated (Voboam model) baroque guitar we made in 1990, which used to belong to Stephen Stubbs (he traded it for a more recent model from us three years ago). Paul borrowed it from our exhibition display while one of his own guitars was still in clamps from the repair work. We're sure that René Voboam would have been amused. 3. Vihuela in e' (Own design, as above)

Six courses, design and construction options as No 1. above, also available

with the option of 4 additional cut-in rosettes. This low-pitched instrument

is useful as an accompaniment instrument for Vihuelista pieces. £4300

This model is also available with the radiating back design option of

No 1. above. 4. Vihuela in a' (own design; based on Paris, Cité de la Musique No. E.0748)

Six courses; vaulted, very deeply-fluted 7-ribbed back (of identical

construction to the Chambure vihuela below, with double-curved, bent

ribs, in figured walnut or figured mahogany, with matching sides; neck,

pegbox and heel (of one-piece construction, along with the neck block)

of cypress or cedrela odorata ('cigar-box cedar', a member of

the mahogany family – originally discovered in the Carribean and

Mexico); ebony fingerboard; brazilwood pegs; rosette available either

cut-in like a lute, or using the Chambure design, in 2 thin layers of

cypress with parchment trefoil decoration behind; (another design is

available, taken from a photograph given to us by Robert Spencer, of

the rosette from an early Spanish guitar; this has one layer of wood

and one layer of parchment); narrow bridge with bone finial ends.

We have decided to offer this instrument and No. 5 with either a composite, set-in rosette, similar to the Chambure instrument's or the one shown below, or with one which is carved into the wood of the belly, like a lute; we took our cue from the Seville Ordenanzas of 1527, as well as contemporary Ordenanzas from Granada and Mexico City, which allow rosettes to be either carved or assembled and set-in: incomes or encomes. There is some doubt as to exactly what encomes means, but it is generally accepted that encomes very strongly suggests engomes, probably meaning glued – thereby implying a rosette assembled from wood & parchment. For the most recent version of this vihuela, we've used the design below, which is taken from a photograph given to us many years ago by Robert Spencer, of the rosette from an early Spanish guitar; it seems very appropriate stylistically, and since it has been dated to the late sixteenth Century, it is sufficiently contemporary with the historical, first flourishing of the vihuela.

The rosette shown above – made from one layer of fruitwood and one layer of parchment – perhaps demonstrating what is meant by 'engomes' – is available as an option with this design. An a'-tuned vihuela of around 540mm string length needs a larger body cavity than, say, that of the Dias guitar in the Royal College of Music (see the guitars section for details); this is because the guitar, with its re-entrant tuning giving a high 5th course and an octave on the fourth, does not have need of a 'bass' response in the same way as a vihuela of this size does. Andrew Maginley – a very experienced early guitar specialist – commented, having played a version of the Dias which we made in the summer of 2003, that a vihuela would probably need a larger body to work properly and have the kind of evenly-balanced response of the larger vihuelas of this type that we have built.

The images above show the general proportions and plantila of the a'-tuned version of the Chambure vihuela we have developed; the soundboard of this instrument is made from a very hard, crisp and responsive piece of haselfichte, the characteristic grain of which is clearly visible here. Therefore, although we looked to the Dias for general inspiration, we knew that a vihuela based on its body proportions and volume simply does not work – as anybody who has played a vihuela built directly on the Dias model recognises; many attempts have been made over the years by various makers to build a vihuela based on the Dias, and none of them have really worked very satisfactorily. This instrument on the other hand does, as Doug Goodhart – the owner of the first of these models – and vihuela specialist Ariel Abramovich, Anna Langley and Denys Stephens noted; Ariel played the second version extensively when he was in London at the recital he gave on the 5th December 2004 at the Peacock Yard Open Studios event. Although it is likely that Belchior Dias also made vihuelas, his 1581 instrument was clearly designed as a guitar rather than a vihuela; it has a shallow body and is much narrower proportionately than the Chambure (see the image below the description of No. 6 further down this page); although inspired by Dias' exquisite little five-course guitar, we knew from experience that a wider and deeper body was necessary for a six-course vihuela of the same string length. However, should a true vihuela by Dias ever surface, it would be a wonderful discovery indeed.

The 6-course version of No. 4 shown above was made in August 2004 for Douglas Goodhart, of Mission, Kansas USA. 5. Vihuela in g' (own design; based on Paris, Cité de la Musique No. E.0748)

Six courses; vaulted, very deeply-fluted 7-ribbed back (of identical

construction to the Chambure vihuela below, with double-curved, bent

ribs, which are deeper across their width at 16mm compared to the Chambure's

10mm) in figured walnut, with matching sides; neck, pegbox and heel

(of one-piece construction, along with the neck block) of cypress or

cedrela odorata ('cigar-box cedar', a member of the mahogany

family - originally discovered in the Carribean and Mexico in the early

16th Century); figured afzelia fingerboard; brazilwood pegs; rosette

available either cut-in like a lute, or using the Chambure design, in

2 thin layers of cypress with parchment trefoil decoration behind; narrow

bridge with bone finial ends; bone panel lines at lower junction of

side ribs. £4800

The very deeply-fluted, double-bent back ribs – made from 7 consecutively-sawn slices of highly-figured walnut – are shown to dramatic effect in these images. We wanted to keep the design simple and elegant for this, the first of our 'evolution' versions of the wonderful Chambure original. An ebony example will follow later, when we can find the time in a busy schedule to make one. 6. The 'Chambure' Vihuela (formerly collection of Madame de Chambure; Paris, Cité de la Musique No. E.0748)

Six courses; vaulted, deeply-fluted 7-ribbed back (of identical construction

to the Belchior Dias 5-course guitar of 1581 - double-curved, bent ribs)

in Cuban mahogany; matching sides; neck, pegbox and heel (of one-piece

construction, along with the neck block) of cypress; walnut fingerboard

stained black (as original, or in ebony); brazilwood pegs; unadorned

soundboard with beautiful rosette in 2 thin layers of cypress with parchment

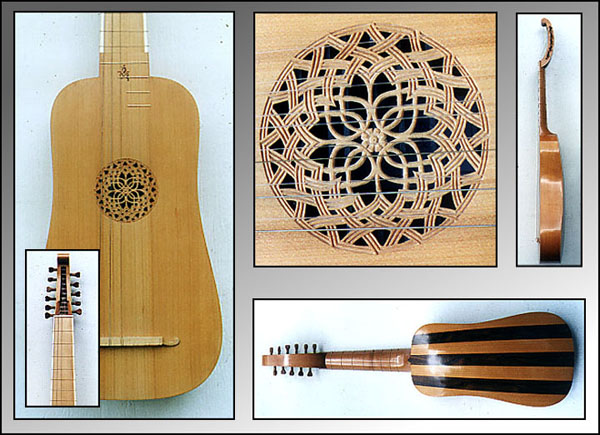

trefoil decoration behind; narrow black-stained bridge. The composite image below shows our prototype copy; this instrument has been strung with Nicholas Baldock's Kathedrale gut strings since March 2002; in December 2002, it travelled to Mexico City and back, remaining in tune and up to pitch throughout. The structure of its body is absolutely stable and strong, and having made several very successful versions of this instrument now, we are convinced that the strength and lightness inherent in this construction was what inspired the original concept.

We finished this close copy – indeed the first proper modern copy of this instrument – in May 2001, having measured and photographed it in Paris when it was open in April 1999. It has Cuban mahogany back and sides, cypress one-piece neck and peg box, a wood and parchment rosette, and a 646mm string length. We were the first modern makers to arrive – via our own efforts and initiative, and working independently – at a proper, reliable and consistent solution to the tantalising challenge represented by its unique double-bent rib back construction. 7. Vihuela in e' (own design; based on Paris, Cité de la Musique No. 259)

Six courses; vaulted, very deeply-fluted 7-ribbed back (of identical

construction to the Chambure vihuela below, with double-curved, bent

ribs, in Cuban mahogany or figured walnut, with matching sides; neck,

pegbox and heel (of one-piece construction, along with the neck block)

of cypress or cedrela odorata ('cigar-box cedar', a member of

the mahogany family – originally discovered in the Carribean and

Mexico); ebony fingerboard; brazilwood pegs; rosette available either

cut-in like a lute, or with one layer of fruitwood backed with one layer

of parchment filigree (like that used in No. 4 above) or using the original

Chambure design (in 2 thin layers of cypress with parchment trefoil

decoration behind); narrow bridge with bone finial ends. This low-pitched instrument – like No. 3 above – is useful as an accompaniment instrument for Vihuelista pieces. We also offer this instrument with either a composite, set-in rosette, similar to the Chambure instrument below, or with one which is carved into the wood of the belly, like a lute; we took our cue from the Seville Ordenanzas of 1527, as well as contemporary Ordenanzas from Granada and Mexico City, which allow rosettes to be either carved or assembled and set-in: incomes or encomes. There is some doubt as to exactly what encomes means, but it is generally accepted that encomes very strongly suggests engomes, probably meaning glued - thereby implying a rosette assembled from wood & parchment. 8. Discante in c" (Own design, following Juan Bermudo's Declaración de Instrumentos Musicales, 1555)

Six courses, very similar in design to No 1., with a single rosette

in wood and parchment. £4200 (inlaid fingerboard £500 extra)

The instruments shown above have backs and sides made from cypress striped with walnut, with one having a fingerboard made from a marquetry of walnut and boxwood (based on a painting by Juan de Juanes [1523-79] La Trinidad con querubines y ángeles in the Convento de Santa Clara, Gandia, Valencia). In the 2 images above left and centre, 6 and 7-course versions are shown. The image above right shows a 6-course discante next to a larger vihuela (No. 1) for comparison. Bermudo says that the Discante is the perfect instrument for playing his pieces (and indeed its short string length makes possible the playing of several 'difficult' pieces which would be a struggle for some players, even on a Vihuela tuned in a'). He goes into detail in his description of the instrument, being quite specific about the exact string length - he tells the reader to add together the 2 lines he has drawn along the border of the page, in order to know exactly the string length he intends - which is 468mm. We have designed an instrument following Bermudo's instructions, which is nominally tuned to c'', although some players prefer to tune to b' (assuming a'=440 Hz) This instrument has the depth of sound and clarity of its larger counterparts, and indeed sounds like the upper register of Vihuela No 1 above. 9. Viola da Mano (Based on the engraving of Giovanni Filoteo Achillini by Marcantonio Raimondi)

Six courses; vaulted back of 7 ribs in cypress and walnut; sides in

cypress; one-piece neck and pegbox in maple, pearwood or walnut; boxwood

fingerboard edged with bone; heart-shaped pegs in brazilwood, or alternating

brazilwood and ebony; single, cut-in rosette.

This example has a back made from cypress striped with walnut, with cypress sides; the heart-shaped pegs are made from pernambuco, the fingerboard is boxwood edged with bone. Owned by Fred Bone, Macon, Georgia. £4400

The

example pictured directly above – shown next to a Chambure vihuela

model for comparison – is slightly different from the version in

the images further up, in that it has its back made from 4 walnut ribs

and 3 cypress. Owned by Professor Fred de Wolff, of Amsterdam.

A 'pyramid' of vihuelas, showing the comparative sizes of No.4 (top) No.5 (middle) and No.6 (bottom). Materials & construction The researches of Antonio Corona – Alcalde have revealed much important information about the materials used in the construction of vihuelas; we learn, for example, that brazilwood – as defined by Covarrubias in 1611 – is "a certain wood from the Indies, very heavy with a bright or fire-like colour (encendido) as a live coal (brasa) ", whose sawdust was used to dye cloth, and whose timber was used in the construction of musical instruments. This is particularly interesting, because we know that the original name for Brazil (as it appears on pre-Columbian maps) was Santa Maria di Cruz, and that upon the discovery of what we now call Pernambuco (caesalpinia echinata) growing there, the country was re-named Brazil, after the wood used to make dyes which the Europeans had previously traded from the Arabs, who were, in fact, obtaining a related timber, Sappan (caesalpinia sapan) from the East Indies. The discoverers of brazilwood supposed that they had at last found where the Arab traders were obtaining the stuff ! The Portuguese explorer Pedro Alvares Cabral first brought the timber to Lisbon in 1500; much of the wealth of Portugal for the next 350 years was based upon the incredible purple-red dye produced by the wood; it is very likely that instrument makers were using it from very early on. The Spanish also referred to the timber as legno di Santa Maria and later on as Legno del Brasile. Amongst other materials mentioned in the archives are walnut and ebony; the Belchior Dias guitar of 1581 has an ebony neck and pegbox, whereas Pablo Nasarre, in Escuela Musica, (Zaragoza, 1724) states that walnut is preferable to ebony for the body of the vihuela, because "ebony has more dryness than moisture", while walnut "is not only strong but warm and moist". Antonio Corona informs us that an inventory of Princess Joanna the Mad, compiled in 1545, lists as item No.36: "A vihuela, the back made of alternating strips (quarteada) of Brazil and white wood (madera blanca) and the sides (cercos) of ebony, with the name of go de Rojas written between the pegs, valued at eight reales . . .". Further references are to Queen Isabella of Valois (d. 1573) owning a vihuela with its back made of alternating strips (quertada) of Brazil and white wood, and to the Marquis of Camarasa (d. 1576) as having owned "an ebony vihuela with ribs, alongside other vihuelas about whose construction no comment is made". Ebony is mentioned several times in the Camarasa inventory as the material used for the construction of guitars, as well as vihuelas, for example: "An ebony vihuela with ribs, with its leather case". We are now certain that the phrase "with ribs" – which recurs again and again in these inventories and descriptions – refers to the double-curved construction used in the Chambure vihuela. Cypress seems to be implied by the constant references to madera blanca or white wood; madera blanca is referred to as being used for, inter alia, instrument cases and chests, clavichord cases, soundboards for violones, rebecs and theorbos, as well as for bowed vihuelas (vihuela de arco de madera blanca). True mahogany – sweitenia mahagoni – was originally brought back to Europe as ship's ballast, but its excellent qualities were quickly realised, and it began to be used for making fine furniture and musical instruments. Cuban mahogany is the trade name for any swietenia obtained from the Spanish West Indies, and San Domingo, Puerto Rico and Costa Rica, as well as Cuba, were among the original sources of this timber in the 16th Century. Sabicu (lysiloma latisiliqua), which resembles true mahogany, was often imported mixed with it. The generic term for these timbers was always 'Spanish wood', indicating their traded origins via the Iberian peninsula, although records exist of its use in England in 1597. 'Cigar-box cedar' – cedrela odorata, a member of the mahogany family – originally discovered in the Carribean and Mexico is another material likely to have been used, since it has been known by Spanish and Portuguese guitar-makers for centuries. Since these woods were used in the construction of Iberian keyboard instruments, it seems reasonable to infer that they were also used in the construction of vihuelas. Presumably other newly-discovered timbers, which were being traded from the New World from early on, would have been known and used, including mahogany and other species from the islands and the mainland, rosewoods and sabicu (the last-mentioned used in fine cabinet-making as well as shipbuilding from early times); these timbers all turn up in other musical instruments from the Iberian peninsula, as well as furniture. The recently rediscovered Paris Chambure instrument (see description at No. 6, and the text above) is a paragon of simple elegance, made mostly of native Iberian woods – and clearly a true player's instrument – its neck & pegbox made in one piece of cypress (madera blanca ?) and its body from Zizyphus (zizyphus lotus), the wood of the now-rare tree that yields the Jujube fruit, formerly used in the making of confectionary. It appears to be built according to the 1572 Lisbon Regimiento dos Violeiros, which call for a viola de 6 ord[ne]s de costillas – a 6-course vihuela with ribs of a dark or reddish wood, de pao preto ou vermelho – which could succinctly describe Cuban mahogany, Zizyphus / Jujube – and this vihuela. There remains the other obvious interpretation of the word vermelho, that is to say Kingwood (dalbergia cearensis) which is what the earliest surviving guitar, the Belchior Dias instrument of 1581 has its sides and back made from. The modern Spanish word for Kingwood is violeta. Decoration The Jacquemart-Andrée 'Guadalupe' vihuela appears to have been built as a guild entry-examination masterpiece, since it follows closely the rules outlined in the Examen de Violeros found in the Ordenanzas de Sevilla (1502) which call for the would-be master, or oficial to be able to build a large vihuela of pieces, with a carved rose and good inlays. Almost identical regulations were in place in Granada in 1529 and further afield in the New World in Mexico City in 1568. The Portuguese regulations were published in Lisbon in 1572 as the Regimiento dos Violieros. The jigsaw construction of the sides and fingerboard of the Jacquemart-Andrée instrument, and its radiating sunray-design back of alternating dark and light woods are available on Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 5. above. Did Bridget Riley and other 'Pop' artists of the 20th Century know about this design ? Hmm. Vihuela soundboards seem to have been frequently adorned with marquetry decoration, in the form of inlaid contrasting woods and other materials such as plain white bone as well as green-stained bone, for example (a material also employed, interestingly, in the fabulous lira da braccio by Giovanni d'Andrea, made in Verona in 1511 {Vienna KHM No. C94 } where it is used in fingerboard inlays as well as soundboard inlays). The idiosyncratic nature of these inlays, which seem to range from a single motif between the rosette and fingerboard, to motifs in all 4 corners of the soundboard (and more, as the lavishly-inlaid Jacquemart-Andrée instrument demonstrates !) were well-enough known for a traveller in Venice, in the Viaje de Turquia attributed to Cristóbal de Villalón, to describe mosaics he sees there: ". . . thus, over this figure they place their small square-shaped pieces, as the violero does with his inlays ". The style and execution of the inlays of the soundboard in the Jacquemart-Andrée vihuela are very similar to the eleven motifs – also 'square-shaped' – found on the anonymous bass viol in the Hill Collection, in The Ashmolean, Oxford (Hill No.3), in their use of green-stained bone; they are also very similar to those found on a harp in the Wartburg, Eisenach. This perhaps suggests an interesting cross-fertilisation of decorative design, or possibly a common origin or source for the inlays. Mosaic inlays of the style used in the Jacquemart-Andrée instrument, and in many iconographic examples, are available as an extra option, and are priced according to their number, complexity and materials. Our fluted-backed vihuelas – some players' reactions and feedback Since completing our prototype copy of the Chambure vihuela – over four-and-a-half years ago now – we have exhibited it in Regensburg, Bremen, Utrecht, Herne, Berlin, Brugge, Mexico City and Vienna. This unique and exciting instrument has attracted considerable interest, resulting in several orders, including from players who already own one of our flat-backed vihuelas or violas da mano. It has a wonderfully bright and powerful sound, with a harp-like clarity. Its pitch of f# is exactly what would be expected with gut strings at a string length of 646mm, and the fact that f# is also the resonant note of the body cavity (when this note is sung across the rosette) seems to demonstrate that this was the intended pitch of the original maker. The 'Evolution' versions have expanded upon the original's qualities, taking them to a further stage of development and refinement, with the resulting instruments having what many have described as a ravishing sound. All of our regular contacts in the professional world – including Stephen Stubbs, Paul Shipper, Mike Fentross, Andrew Maginley, Michiel Niessen and Radamés Paz – and of course Antonio Corona, whose insights and inspirations set us on the path to vihuela-making in the first place – have declared themselves convinced and impressed by these instruments. 2001 Eloy Cruz, the well-known Mexican vihuela player, first tried our original prototype copy at Regensburg Tage Alter Musik 2001, 4 weeks after its completion, and wondered if its harp-like sound might go some way to explaining the possible origin of the Mudarra piece in imitation of the harp-playing of Lodovico, if this is what vihuelas sounded like. Stephen Stubbs played it in Bremen in August, and endorsed this view, saying that this instrument sounded and felt just right. Several players at the Utrecht exhibition tried it and were very impressed. A couple of months later, at the Berlin exhibition in October, Mike Fentross sat down to play the instrument – now strung throughout in gut – and had to be dragged away from it by a colleague who wanted him to go off to a rehearsal. Franco Pavan also had the chance to try the instrument, which produced a huge grin on his face, before he too, had to reluctantly put it down and go to a rehearsal. 2002 When we showed our prototype instrument to Xavier Diaz in the summer of 2002, he remarked upon its lightness, clarity and projection qualities (played in St Johns Smith Square, London, the gut-strung vihuela could be heard quite clearly right at the back of the hall). Xavier told us he had seen other versions of this instrument, looking superficially like the 'Chambure', but much heavier – presumably carved from solid pieces, rather than bent. Like English viol fronts, the whole point of the Chambure's construction is that you bend, not carve. Antonio Corona had the opportunity to play our prototype copy of the instrument, during Stephen's visit to Mexico City in December 2002, and this experience confirmed his view that the Chambure vihuela in the Cité de la Musique collection is indeed what we have all been looking for. He is looking forward to trying one of the evolution models we are currently building, which have a more manageable string length of 590mm; his former student Radamés Paz, now based in Den Haag, is planning a CD recording using one of these new instruments, in 2006. 2003 Several lutenists playing in the concerts at Regensburg Tage Alter Musik 2003 also commented on its strong, clear sound; the Chambure original is a highly significant and very interesting discovery, and its sound, when properly made, is clear and bright, and not at all 'introverted and delicate' as some who have made versions of it suggest (which seems to us to be an admission that an instrument has little sound, and is therefore a bit pointless). At the exhibition, young Berlin-based lutenist Andreas Arend – a former student of Nigel North's – spent a long time playing the gut-strung prototype and liked its sound very much; he was amused when told of the comment made by somebody else who has made a 'copy' of this instrument, that their version had an 'introverted' and 'delicate' sound. He wondered how they had managed to produce an instrument that had these 'qualities', when our version, properly-built and strung with gut, was quite clearly anything but 'introverted' or lacking in sound. Another vihuela and baroque guitar specialist – Paul Shipper – also playing in the concert series at Regensburg, succinctly commented that for a maker to describe an instrument as having an 'introverted' sound was a tacit admission that it has, in fact, no sound. Aleksandar Sasha Karlic – the director of Theatrum Instrumentorum – also played the instrument for a long time, and said it was the first time he'd played a convincing vihuela. At the subsequent Utrecht exhibition of August 29th-31st, Andreas Arend played the evolution version of this instrument alongside the prototype, and declared that this is what vihuelas should sound like – clear, strong, and articulate. The Cité de la Musique institution in Paris – who own the original – commissioned a copy of the instrument for their collection. 2004 At the January Vienna Resonanzen 2004 festival, we received an order for a copy of the Chambure from a long-standing fan of Julian Bream's, who played the instrument and was surprised by the clarity, power and balance of its sound; having until this point always been a classical guitar player, used to 'vihuelas' with metal frets and high-tension guitar-like stringing – which were guitars in all but name, being passed-off as vihuelas – our new customer was convinced by the instrument's qualities. We fitted his order into a gap which had been reserved in our waiting list for late 2004, and the new instrument was delivered to him at Resonanzen in January 2005. Jacob Heringman visited the workshop in March this year, and having spent some time playing the two examples we keep here – our prototype copy of the Chambure and the first evolution model – was very impressed by their clarity, focus, balance and power. Both instruments are strung throughout with Nicholas Baldock's Kathedrale-brand gut. We completed a new 590mm string length 'evolution' model in May 2004 for Craig Hartley, former Senior Assistant Keeper (Prints) at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Craig subsequently wrote: " Dear Stephen and Sandi, I spent a happy weekend playing through vihuela music with high positions. The more I play, the more impressed I am with the instrument. I was expecting the lovely tone, the clarity and balance of voicing; but as I get used to it I'm also excited by the potential to colour the sound expressively. Many many happy hours ahead. Thank you". At the Regensburg Tage Alter Musik 2004 exhibition in late May, Christina Pluhar and Axel Wolf - both playing in the concerts (with L'Arpeggiata and La Capella Ducale e Musica Fiata Köln respectively) tried the two vihuelas we had with us (the original prototype - first shown at Regensburg in 2001 - and the first evolution version); they both said they thought the vihuelas sounded fantastic, and looked beautiful. Christina seemed particularly delighted when she played the evolution version.

Shown above is the recently-designed a' vihuela (foreground in both images) next to our original copy of the Chambure instrument for comparison; although here it doesn't look much smaller – the perspective shift produced by the camera lens used causes this effect – its string length is 540mm (compared to the original's 640) with a ten-fret neck. We kept the second version built (made from identical materials, except for the fingerboard) which is available for players to try and compare with examples of the other two larger instrument here in the workshop. It will not be offered for sale, but will join our original 2001 prototype copy of the Chambure and the first 'Evolution' version as part of the permanent collection of instruments we keep in the workshop. Players are welcome to visit and try this trio of vihuelas. Radamés Paz, upon playing the new a'-tuned vihuela at the Utrecht festival at the end of August, just after it had been strung for the first time, exclaimed: "This is the one !". He was convinced by its size and string length, which of course enable the player to negotiate the more demanding left-hand stretches of the repertoire. Andrew Maginley and Stephen Stubbs also tried the new instrument and were very impressed and convinced by it. 2005 After this instrument was sent to its new owner in Kansas City, Doug Goodhart, in September 2004, he emailed us after experimenting with different strings, saying: " The vihuela is sounding great. It has very good projection and a warm, clear and lovely tone. In short, your vihuela is everything I had hoped it would be and we are getting along quite well. Everyone who hears it thinks it has a strong, lovely sound. The music community here is fully impressed. Thanks again for a wonderful instrument and all the best ". Doug sent this message, on January 25th 2005: "Just a note to let you know how much I am enjoying the vihuela, we seem to have 'bonded' quite well and it is a joy to pick up and play each and every day (so much so that some of my other music is not getting a lot of attention). This vihuela is really coming into its own, developing beautifully in all registers. And I will say again that the neck is just what I was looking for. The concert in Cleveland went very well, and as predicted I received two other firm bookings with some other possible bookings. I am also working on a one-man presentation of music from 1500 to the present, through various cultures. The vihuela will feature prominently in that presentation as well. All the best, Doug". NYC-based composer and lutenist Michael Calvert, visiting the workshop in November, marvelled at the clarity, subtlety of tone and power of the 600mm 'Evolution' instrument, and wants one asap. Several players attending the Regensburg 2005 Tage Alter Musik and Utrecht festivals had the opportunity to play the instrument, and they all enjoyed doing so. 2006 Players visiting the January Resonanzen exhibition had the opportunity to try the three different-sized fluted vihuelas that we keep at the workshop and take to exhibitions, and further orders resulted. Later in 2006, US guitarist Harvey Molloy (who studied with Pujol) ordered an instrument in g', following a visit to the workshop. A player who bought an 'on spec' 10-course lute from us in December tried the same g' fluted-back vihuela, and said that this would be next on his shopping-list. 2007 We received further orders in 2007 – four, in fact – for various sizes of fluted-back vihuelas, as well as for the No. 1 'Guadalupe' model, from Eligio Luis Quinteiro, the up-and-coming Spanish player based in London; Eligio was able to try several models at the workshop, but finally decided upon a flat-back version, as he felt that the 'Guadalupe' model was more 'Spanish', the fluted-backed instruments being perhaps more 'Portuguese', in his opinion. We fitted Harvey Molloy's order into one of our 'gaps' in November 2007. 2008 More favourable reaction continued to be attracted by these instruments, and we built a version of the 'Evolution' model for Köln-based lutenist Vanessa Heinisch, a former student of Konrad Jünghanel, in May this year. 2009 The smaller 'Evolution' and a'-pitched versions of this model continued to attract interest and orders at the Vienna Resonanzen and Regensburg Tage Alter Musik festivals, as well as at the Utrecht vihuela symposium, where we showed them over the weekend of August 30th–31st. The symposium was held under the auspices of the Sociedad de la Vihuela, as part of the Utrecht 2008 Oude Muziek Festival. The symposium was complemented by an exhibition held in the Kikker Theatre, Utrecht. 2010 Work on the copy of the original for the Paris Cité de la Musique museum was almost completed by the start of 2010, with evaluation and acoustic tests on the instrument conducted by scientists from the Musée in late February and March. Following further consultations with the Musée, the instrument was completed and delivered in early September. 2011 Only two fluted-back vihuelas were made in 2011, both instruments tuned in a'. 2012 Three fluted-back vihuelas were made in 2012, tuned in g'. 2013 One fluted-back vihuela was made in 2013, it was mainly a year for guitars & lutes. 2014 As in the previous year, only one fluted-back vihuela was made in 2014; a second, flat-backed vihuela was made for Australian artist and sculptor Ammun Luca, for whom we had previously made a 6c lute modelled on the Georg Gerle original; both vihuelas were tuned in g' (a'=415Hz) and strung throughout in gut. The workshop fire in mid-June stopped us in or tracks for the rest of that year. 2015 –2017 In the aftermath of the workshop fire we have three fluted-back vihuelas on order, one 'sunray'-backed instrument and a vaulted-back viola da mano, as we catch up with delayed work one-by-one. The original Paris 'Chambure' instrument The two close-up images in the top row below (from photos we took in April 1999) show details of the original instrument, and clearly reveal toolmarks which we are certain were from the hands of its maker: deep scratch marks around the heel, and across the junction of the side ribs at the bottom. These were probably produced by the use of files on the heel, and probably sharkskin or dogfish skin – used as an abrasive – at the rib junction.

The lower 2 images (above) show the inside of the back of the original on the left, with, to its right, the inside of the back of our first copy; the little diagonal strips across the ribs are parchment, as are the corner strips between the side and back ribs. The slender spruce bottom block and the one-piece neck & slipper block are clearly visible in both instruments; the carving and shaping of the original's slipper block are so similar to that of the Dias guitar, that we are sure they are at the very least from the same workshop, if not the same hand.

The two images above show the original instrument's rosette (the missing section to the right in each view helps to orientate the viewpoint – the soundboard was rotated through 180û between the two photographs). Its structure – two layers of wood backed by one layer of parchment on the inner surface – is clearly visible; the parchment layer carries cut and punched filigree detailing. The outer, upper surfaces are covered in a thin layer of paint or possibly gesso (was the original intention to gild it ?) whilst the inside view shows the parchment curling away from the timber in places, with the undulating distortion of the rosette due to the effects of age and fluctuating humidity unmistakable. Some other makers offering versions of this wonderful instrument have – despite the unequivocal evidence reproduced here – claimed that this interesting rosette is entirely made of wood, and then bought-in wooden versions of it. When we copy this rosette, we do it properly – respecting and following the original design, using parchment for the lower decorative layer – and we make it ourselves, we don't outsource it. Or for that matter obscure its beautiful design with paint. An important discovery – a true player's instrument The original Chambure vihuela seems to us to be unquestionably a 'player's instrument', made as it is from simple materials without decoration; it is a very inspiring instrument to work from, as inspiring for us as, say the 'Messiah' Stradivari violin has been for generations of violin makers. It is in our opinion an instrument of equal significance and importance. This beautiful, stunning instrument seems to have been made quickly and confidently – as all the best old instruments were, with absolute command of proportion and line – yet with apparently little concern for surface finish finesse. However, it is interesting to contemplate the fact that it was made on the one hand from humble and modest materials, without extraneous decoration – yet the virtuoso construction techniques employed to create its unique back were clearly developed for very sound musical and acoustical reasons. Otherwise, why go to such trouble on an otherwise plain and simple instrument ? It appears to be built according to the 1572 Lisbon Regimiento dos Violeiros, which call for a viola de 6 ord[ne]s de costillas – a 6-course vihuela with ribs of a dark or reddish wood, de pao preto ou vermelho – which could succinctly describe Cuban mahogany, and the appearance of this vihuela. We are certain that its complex, subtle concept and construction represents a style of vihuela building perhaps more widely-known in the 16th Century than we have hitherto realised. We think it is likely that the large number of listings in contemporary inventories and other archives to a vihuela with ribs is actually referring to this type of back construction, rather than a way of describing, say, the flat or vaulted back of an instrument made of several strips. We are planning to build an ebony example, prompted by the inventory of the Marquis of Camarasa. who died in 1576, who is mentioned as having owned an ebony vihuela with ribs. This is not the only such specific reference. Was this type of construction clearly understood and common currency in the technical repertoire of stringed instrument makers, and widespread across Europe in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries ? We are certain that it was – and that there is a clear parallel between this construction and contemporary English bent-front viol soundboards. Working timber staves in this way – simultaneously related to, yet quite different in concept from the simple bending required to produce lute ribs or guitar and vihuela sides – using complex curves to achieve a carefully-calculated result, seems to have been very much part of the repertoire of the old Iberian instrument makers. Stephen was instrumental in discovering and demonstrating – 35 years ago, back in 1982 – whilst measuring and drawing a 1690 Richard Meares bass viol, made in London, that the bellies of this and other English viols were constructed from several bent staves, and not, as most viol makers in modern times had supposed, carved from solid slabs, like a cello or violin front. And Sandi was able to demonstrate to the distinguished viol maker Dietrich Kessler how these staves might be jointed, by showing him how she fits lute ribs, to achieve an invisible join. Making a structure like a belly (or back) this way allows great strength to be obtained from thin sections, and there are obviously acoustical implications for a 'sprung' structure. Antonio Corona, the distinguished vihuela researcher and scholar, has commented: " In fact, the first thing that struck me when I examined it was the feeling that this was, finally, a musician's vihuela, as opposed to the other two extant instruments". As well as feeling that this vihuela represents a player's instrument, he has also made the following very interesting observations regarding its double-curved back: "The regulations of the guild of vihuela makers of Madrid, late in the sixteenth and early in the seventeenth centuries, mention either 'vihuelas aconvadas' (convex) or 'vihuelas tunbadas' (that is with a bent back in the shape of a tomb, tumba) and 'acanaladas' (fluted). Both the Dias guitar and the Chambure vihuela answer well to these descriptions, and I must agree to your suggestion that both belong to the same school of construction, that is my own opinion as well". Anybody offering the unsuspecting player a version of this instrument with its back ribs carved from the solid, or only shallowly-fluted, or even built like an Italian vaulted-back guitar (ie from thick ribs which are scraped to produce a fluted effect – but remain flat on their inside surfaces) is completely missing the point, and fooling the player.